Here’s an in-depth guide containing everything you need to know about shotgun gauges, to include the differences between 12 gauge vs 20 gauge and other popular bore sizes.

While many hunters know a little bit about shotgun gauges, I think that most people would likely agree the subject can be really confusing. That’s perfectly understandable because the way shotgun gauges are classified is counterintuitive at first glance. It’s also based on an old, outdated measuring system that has gradually evolved over the years.

The end result is something of a convoluted mess that the average hunter can really struggle to make heads or tails out of. Not surprisingly, there are even more misunderstandings and misconceptions regarding shotgun gauges than most other subjects concerning firearms and ammunition.

For that reason, I’m going to discuss the ins and outs of shotgun gauges in detail in this article. I’ll go over the history of shotshells, how they got their naming convention, compare and contrast some of the more popular shotgun gauges (the 12 gauge vs 20 gauge in particular), and provide some recommendations on the best uses for each.

Before we get started, I have an administrative note:

Some of the links below are affiliate links. This means I will earn a small commission (at no extra cost to you) if you make a purchase. This helps support the blog and allows me to continue to create free content that’s useful to hunters like yourself. Thanks for your support.

Additionally, I recorded an entire podcast episode on this exact subject. If you’d rather listen than read, click the appropriate link below to listen to this episode on your preferred podcasting service.

Shotgun Gauge Podcast

Apple | Google | iHeart | Spotify | Stitcher

Shotgun Gauges: History & Naming Convention

To really understand the naming convention of shotgun gauges, we need to head back to the days of black powder.

Back then, cannons were named in accordance with the mass of the projectile they shot, not by their bore diameter. For instance, a 12 pound cannon (aka a 12 pounder) shot a round ball that weighed approximately 12 pounds. The same principle applied to 8 pounders, 6 pounders, 4 pounders, etc.

Shoulder fired weapons that fired projectiles weighing less than 1 pound used a closely related system. Continuing down that same line of thought from 12 to 8 to 4 pound projectiles, the naming convention switches from “pounds” to “bore” when we drop below 1 pound of lead. Large bore black powder rifles were named in this manner and this also is where the system for measuring shotgun gauges comes from.

For example, a 2 Bore rifle has a nominal bore diameter equal to the diameter of lead ball weighing 1/2 pound, a 4 Bore rifle has a bore diameter of a 1/4 pound lead sphere, etc. So, we have a system where a 10 gauge shotgun has a bore diameter the same size as a 1/10 pound ball of lead and the diameter of the barrel on a 12 gauge shotgun is the size of a 1/12 pound lead ball.

If they’re made out of the same material, a 12 pound round ball will be larger in diameter than an 8 pound ball.

Well, this is also true with a 10 gauge (or 10 bore) ball compared to a 12 gauge (or 12 bore) round ball.

In short, the smaller the gauge of a shotgun, the larger the bore diameter. This is why a 10 gauge shotgun has a larger diameter than a 12 gauge shotgun, which has a larger diameter than a 20 gauge shotgun, etc.

A different way of saying the same thing would be to describe shotgun gauges in terms of the number of lead balls of a certain diameter necessary to weigh 1 pound. So, 12 round lead balls of 12 gauge diameter would weigh 1 pound, but since they’re smaller, it would take 20 balls of 20 gauge diameter to weigh a pound.

There is one exception to this rule: the .410 bore. Sometimes inaccurately described as “.410 gauge” or “36 gauge”, it’s the only shotgun in common use that is named after its actual bore size (.410 of an inch diameter) as opposed to a gauge number. If it were named like all the other popular shotgun bores, it would be approximately 67 gauge.

Shotgun Gauges: Nominal vs Actual Bore Size

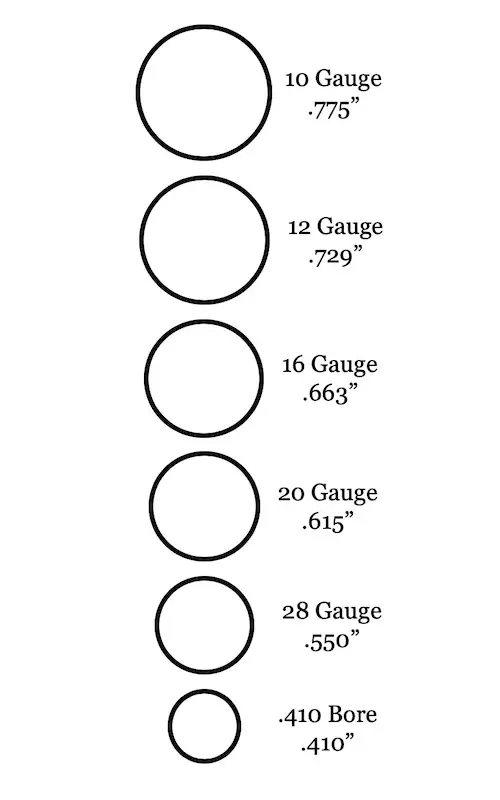

Fortunately, it’s no longer necessary to actually do the calculations necessary to determine the internal diameter of the barrel for the most popular shotgun bores. Just reference the chart below for the nominal bore size of 10 gauge, 12 gauge, 16 gauge, 20 gauge, 28 gauge, and .410 bore shotgun barrels.

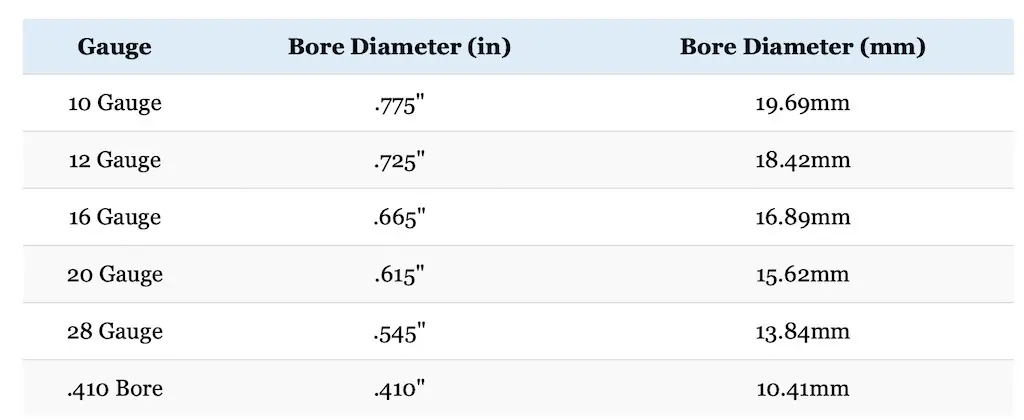

Those numbers are great for making an overall comparison between the various shotgun gauges. However, the actual diameter of the bore will sometimes vary. The Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers’ Institute (SAAMI) standards for those same shotgun bore sizes are listed below.

Note that the published standards are for a smooth barrel and have a tolerance of +.020″ (.51mm).

Shotgun Gauges: Shell Length & Pellet Size

Remember: gauge size only describes the bore diameter of a shotgun. While that’s extremely important, there are many other important characteristics of shotgun shells to keep in mind as well.

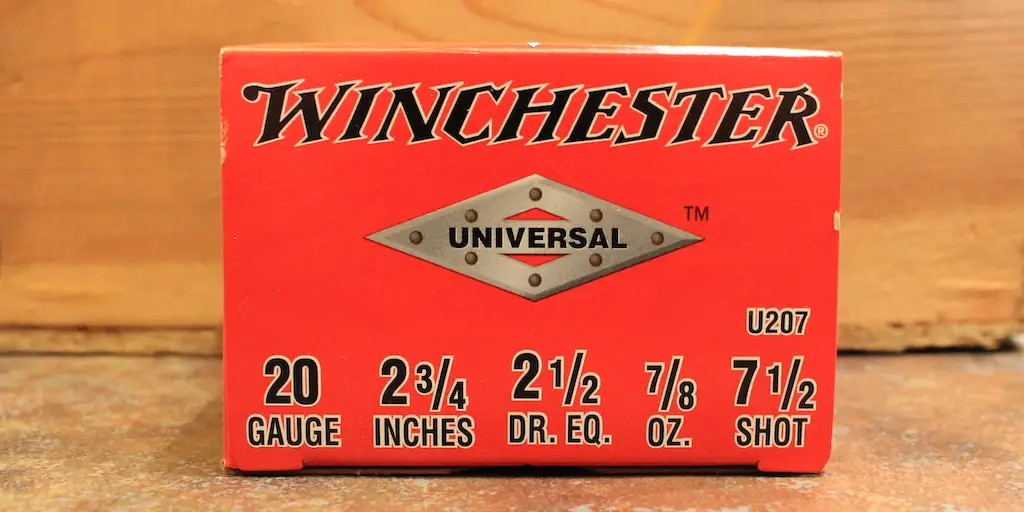

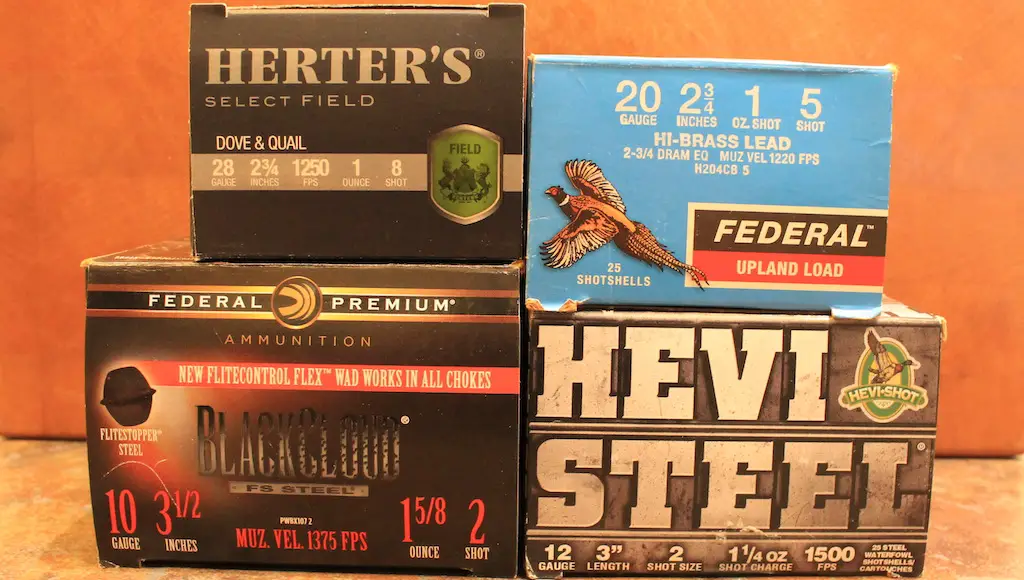

In addition to gauge, shotgun shells also come in varying lengths with different loads of powder, shot weight, shot size, and shot composition. For example, take a look at the photo below of a box of 20 gauge shotgun shells.

This box contains 20 gauge shells designed for use in a 2 3/4″ chamber. The individual shells are loaded with a 2 1/2 dram equivalent of powder and 7/8 of an ounce of 7 1/2 size shot. Winchester markets this particular ammunition for upland bird hunting, sporting clays, skeet, and trap.

Lets break down what each of those things means.

The spot where it says “2 3/4 inches” references the length of one of these shells after it has been fired. They’re usually about 1/2″ shorter when loaded. Longer shells usually contain some combination of more shot and/or more powder for a higher velocity and/or a heavier shot load, so all other things being equal, a longer shell will kick more than a shorter shell of the same gauge.

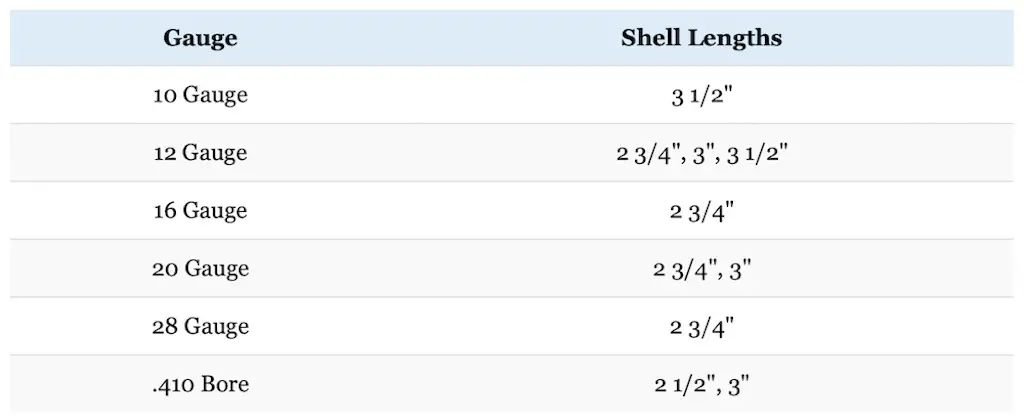

The shell lengths and gauges listed below are standardized by SAAMI and are therefore the most widely available and easy to find. Sizes other than those listed below are sometimes available in limited numbers.

Look on the barrel or chamber of your shotgun to determine the proper length shell it can use. A shotgun with a longer chamber can generally safely use smaller shells, but the opposite is not true. 20 gauge shells are commonly available in both 2 3/4″ and 3″ lengths. So in this case, you could safely fire those 2 3/4″ shells in a 20 gauge shotgun with either a 2 3/4″ or a 3″ chamber.

Aside from shotgun slugs, shotgun shells are loaded with a large number of pellets. The exact number of pellets depends on their size and composition as well as the weight of pellets loaded into the shell.

To determine the size of birdshot, just subtract the shot size from .17″. So, 7 1/2 birdshot is .095″ in diameter (.17 – .075 = .095). This is not the case with other types of shot like BB and buckshot. That being said, while there are exceptions, those other shot sizes larger than .17″ generally increase in size in a pretty uniform manner as well.

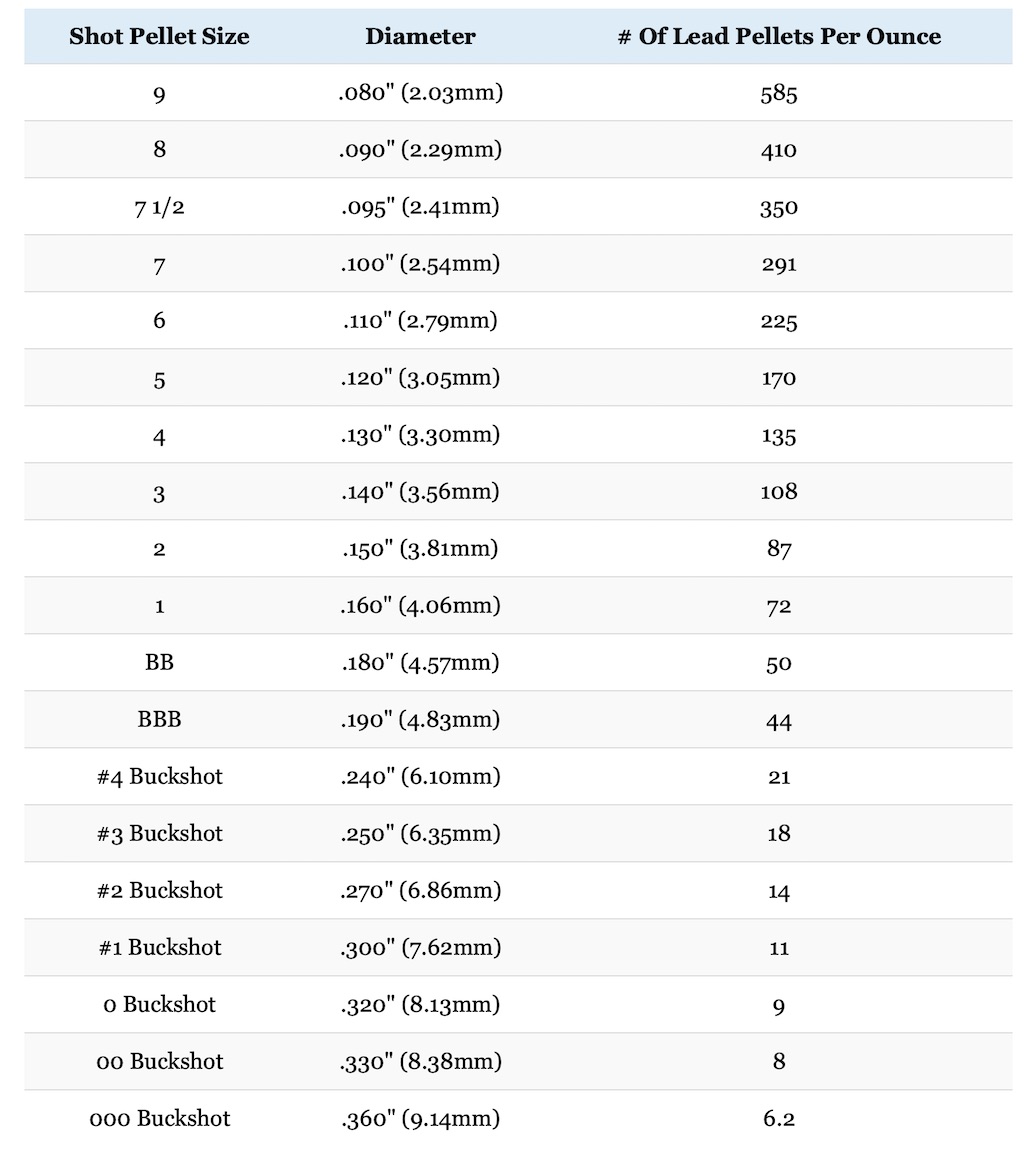

Reference the table below to see the diameter of some of the most common shot sizes as well as the approximate number of lead pellets of that size that weigh one ounce. As you can see, the number of individual pellets in an ounce decreases as the pellets increase in size.

Some boxes of shotgun shells state the composition of the pellets. For instance, lead free, non-toxic shot is mandated for waterfowl hunting in North America. So shells marketed for waterfowl hunters will state that they contain pellets made of bismuth, tungsten, steel, or some other sort of alloy that doesn’t contain lead. Additionally, some upland and turkey hunting loads intended for use on larger birds will sometimes use copper-plated shot that’s less likely to deform on impact.

Most shotgun shells are loaded with lead shot and it’s best to assume that’s what you’re dealing with if the box doesn’t say anything about it one way or another. Of the materials commonly used to produce shot, lead is the most dense (with a handful of exceptions, like tungsten). This means that a given number of individual lead pellets will weigh more than the same number of pellets of the same diameter made out of some other material.

With all of those things in mind, we can determine that the box of 20 gauge shells we’ve been talking about contains approximately 306 lead pellets that are .095″ in diameter (350 7 1/2 size pellets in an ounce multiplied by 7/8 of an ounce).

Now we get to the 2 1/2 dram equivalent part.

This area can get particularly confusing, so bear with me for a minute here.

A dram is a unit of mass from the British Avoirdupois weight system that still remains in varying degrees of use in some of the former colonies. Back in the days of black powder, drams were commonly used to measure the amount of black powder in a particular load.

Most people probably know that there are 16 ounces in a pound. Well, there are 16 drams in an ounce. So therefore, there are 256 drams in a pound. Additionally, many gun enthusiasts know that there are 7,000 grains in a pound. This means that there are 27.34 grains in a dram.

So, a 2 1/2 dram load of black powder would weigh 68.35 grains.

A long time ago, somebody somewhere determined that a certain 12 gauge shotgun load firing 1 1/8 ounces of shot with 3 drams of black powder (82 grains) had a muzzle velocity of 1,200 feet per second. If it sounds like a cumbersome way of doing things, you’re right. It’s really confusing, but ever since then, companies manufactured shotgun shells listing the powder load in terms of drams of black powder.

After the transition to smokeless powder in the early 20th Century, ammunition companies continued to describe the amount of powder they loaded in a shotgun shell in “dram equivalents.” It’s an imprecise way of doing things, but they were trying to go about describing the velocity of that particular load in a roundabout way.

Dram equivalents are good for making an apples to apples comparison (all other things equal, a 2 3/4 dram eq. load will have a higher velocity than a 2 1/2 dram eq. load), but that’s about it.

For that reason, companies are making the transition away from listing dram equivalents on shotgun shells and instead publishing the actual velocity of the load like on the boxes below.

You’ll still occasionally run into boxes still bearing dram equivalent markings, but they’re getting less and less common.

Lets be clear here: dram equivalents should only be used for a general comparison between two different shotgun loads. Furthermore, smokeless powder is considerably more powerful than black powder and you should NEVER reload shotgun shells using “drams” or “dram equivalents” of smokeless powder. ONLY reload shells in accordance with the data supplied by a good reloading manual.

Doing anything else can be very dangerous.

Shotgun Gauges: Recommended Uses

Of all the shotguns in the United States, 12 gauge guns are by far the most popular. The 20 gauge comes in second, followed by the 28 gauge and the .410 bore. The 10 gauge and 16 gauge are much less common than the rest, but are by no means rare.

So, which one is best for you?

Well, it depends.

The shot pattern of a shotgun gradually expands as range increases. This makes it easier to hit a target, particularly one that is moving, out to a certain range. Hunters can tighten up the shot spread to a certain extent by using a choke, which is a constriction on the muzzle of the shotgun. However, there always eventually comes a point where the shot pattern is too spread out to guarantee a hit on an object that passes through the shot column.

Additionally, the individual pellets all slow down as they leave the barrel. In general, heavier pellets retain more velocity at longer range and cause more damage than smaller and lighter pellets. However, increasing the size of shot results in fewer individual pellets. So, increasing the shot size comes at the expense of a thinner shot pattern if the total shot weight remains the same.

Shot patterns are traditionally measured by shooting at the center of 30″ circle at 40 yards and counting the number of pellets that hit inside the circle. A dense pattern is ideal for quickly and ethically taking game and means that more pellets hit inside that circle and there aren’t any large “voids” within it.

Certain shotguns pattern better with particular loads. That being said, in general, one way to get a dense shot pattern is to increase the shot weight, like going from 1 ounce to 1 1/8 ounces of shot for example. However, the shot weight can only be increased to a certain degree for a particular gauge and shell length.

This is further complicated for North American waterfowl hunters when using steel shot. Remember when we talked about how lead is more dense than steel earlier in the article? Well, this is why that matters.

Since individual steel pellets weigh less than lead pellets of the same size, hunters must typically use larger diameter steel shot or suffer degraded terminal performance. However, using larger diameter shot results in thinner shot patters. This is why many hunters use 10 gauge and 12 gauge 3″ or 3 1/2″ magnum shotguns, which can fire a heavier load of shot, for ducks and geese.

All other things being equal, a larger bore shotgun with a heavier load of shot will throw more pellets and therefore produce a denser shot pattern at a given range than a smaller bore shotgun with a lighter load of shot.

Hunting larger game animals, like turkey and goose, usually requires heavier loads of larger sized shot. The same goes for taking longer range shots. However, there is such a thing as overkill though and hitting a small creature with a heavy load of shot will cause substantial damage resulting in the loss of much or all the meat. At the same time, the heavier load fired from a larger bore shotgun comes at the price of more recoil.

As you can probably imagine, there’s something of a sweet spot when it comes to shot size and weight for certain game. The skill level of the hunter also plays into the equation.

Robert Ruark summed this up pretty well in his essay The Brave Quail:

The gauge of the gun is an index to the ability of the man to prove his manhood…If it is a 12-gauge, he is so-so. If it is a 16, he is pretty good. If it’s a 20-gauge, he is excellent, and if it a .410 he is bragging.

With all that being said, below are the recommended uses for each of the most popular shotgun gauges.

10 Gauge: The 10 gauge shotgun is primarily used by waterfowl hunters, especially for goose hunting. This is because of the previously discussed advantages of the larger bore and longer shell length offered by the 10 gauge when using non-toxic shot compared to all other shotgun gauges in common use. Its stout recoil coupled with the heavy weight of most 10 gauge shotguns also limits the appeal of that bore size to most hunters.

While there are a few turkey loads currently offered in 10 gauge using #4, 5, or 6 size shot, non-toxic ammo intended for use on ducks (size 2) or geese (BB, BBB, or T size shot) makes up the vast majority of all 10 gauge ammunition currently manufactured.

BUY A HARD HITTING 10 GAUGE SHOTGUN HERE

BUY SOME 10 GAUGE SHOTSHELLS HERE

12 Gauge: The 12 gauge is by far the most popular shotgun size in the United States and possibly the entire world. Produced in just about every type of shotgun from semi-automatics to pump actions and everything in between, the 12 gauge is the shotgun of choice for big game, turkey, waterfowl, upland, and small game hunters. It’s also the #1 choice for home defense as well as for military and law enforcement use.

Indeed, a hunter armed with an inexpensive Remington 870 or Mossberg 500 pump-action shotgun could conceivably hunt almost every species of game in North America by simply changing the barrel, choke, and/or shot size as necessary.

Not surprisingly, 12 gauge ammunition is also widely available in virtually every shot size from #9 up to 000 Buckshot and slugs. Standard 2 3/4″ 12 gauge shells work very well on most species of small and upland game. They’ll also do the trick for waterfowl, turkey, and big game, but the larger 3″ magnum shells are more popular for hunting those species. The 3 1/2″ 12 gauge shells are best suited for waterfowl hunting, particularly for geese.

The 12 gauge is so popular because it’s powerful enough to hunt most species of game, but the recoil of a 12 gauge is much more manageable than the 10 gauge.

A 12 gauge shell also has advantage over the smaller gauges because it has a shorter shot column. Basically, the fatter 12 gauge shell can fit the same weight of shot into a shorter column, which results in less shot deformation as it travels down the barrel. This means that 12 gauge loads will generally pattern better with the same amount of shot when compared to a smaller gauge shotgun.

BUY A GREAT ALL-AROUND 12 GAUGE SHOTGUN HERE

BUY SOME EXCELLENT 12 GAUGE SHOTSHELLS HERE

16 Gauge: While it remains relatively popular in Europe, the 16 gauge never really caught on with American hunters. Most Americans looking for an all-purpose shotgun use the 12 gauge and those looking for a lighter shotgun use the 20 gauge. Several factors contributed to this state of affairs, but the transition to steel shot for waterfowl in particular really hurt usage of the 16 gauge and it’s now one of the least commonly used shotgun sizes used in North America.

That being said, the 16 gauge can do just about everything else almost as good as the 12 gauge, but with a little bit less recoil. While it’s certainly a capable all-around shotgun gauge suitable for deer, turkey, and duck hunting, the 16 gauge is most often used in the United States for hunting small and upland game like pheasant, quail, dove, grouse, rabbit, and squirrel. For this reason, most 16 gauge shells are loaded with #4, 5, 6, 7 1/2, and 8 sized shot.

BUY A NICE 16 GAUGE SHOTGUN HERE

BUY SOME GOOD 16 GAUGE SHOTSHELLS HERE

20 Gauge: Ranking only behind the 12 gauge in terms of popularity, the 20 gauge is by far the most widely used of all the smaller gauges. It’s available in a wide variety of shotgun types (primarily pump and semi-auto) and 20 gauge loads are manufactured in just about every size from #9 all the way up to #2 buckshot loads and slugs.

While the 20 gauge is on the light side for deer, turkey, and waterfowl hunting, it will work in a pinch for those situations. Indeed, advances in non-toxic shotgun ammunition over the past few decades have dramatically improved the suitability of the 20 gauge for waterfowl hunting.

However, the 20 gauge is widely used as an upland and small game shotgun and excels in those roles. The light recoil of the 20 gauge, combined with the fact that it has a much denser shot pattern than the .410 bore, helps explain why the 20 gauge is so popular among small framed as well as younger shooters and hunters. Indeed, the relatively low felt recoil of the 20 gauge also makes it well suited for self defense and makes it easier to take a rapid follow-up shot.

BUY A GREAT 20 GAUGE SHOTGUN HERE

BUY A GREAT 20 GAUGE YOUTH SHOTGUN HERE

BUY SOME EXCELLENT 20 GAUGE SHOTSHELLS HERE

One final thing to keep in mind about 20 gauge shotgun shells is that, regardless of the manufacturer, current production 20 gauge shells are ALWAYS yellow.

Why are 20 gauge shells yellow?

12 and 20 gauge are by far the most commonly used shotgun gauges. For this reason, they are also the most likely to get mixed up. As you can see in the photo below comparing 12 gauge vs 20 gauge shells, 20 gauge shells are considerably smaller than 12 gauge shells.

A 12 gauge shell won’t fit in a 20 gauge chamber because it’s too big. On the other hand, if you attempt to load a 20 gauge shell in a 12 gauge shotgun, the shell will drop through the chamber and get stuck in the barrel. This will obviously cause a barrel obstruction with potentially catastrophic results if the shotgun is subsequently fired without removing the obstruction.

You should never attempt to load any shells of a different gauge into any shotgun, but this is of particular importance with 20 gauge shells.

In addition to the fact that 20 gauge shells are so common, they’re also the perfect size to cause an especially dangerous situation. A 16 gauge shell is big enough that it won’t go far enough down the barrel of a 12 gauge shotgun for a 12 gauge shell to chamber and fire behind it. 28 gauge and .410 shells are small enough they they’ll travel all the way through a 12 gauge barrel without getting stuck.

So, 20 gauge shells are yellow in order to make them easy to identify and to minimize the chances of loading a 20 gauge shell in a 12 gauge shotgun.

28 Gauge: Ranking below the 12 and 20 gauges in terms of popularity, the 28 gauge shotgun is somewhat common in upland game hunting and skeet shooting circles. It’s substantially more powerful than the .410 bore, but still has a very gentle recoil, even in a lighter gun. The 28 gauge is commonly available in a number of lightweight and easy to carry shotguns.

Ammo is far from common, but it’s not rare either. Almost all 28 gauge ammunition options are concentrated in the smaller 6, 7 1/2, 8 , and 9 shot sizes ideal for skeet shooting as well as squirrel, rabbit, dove, grouse, and quail hunting.

BUY A STYLISH 28 GAUGE SHOTGUN HERE

BUY SOME 28 GAUGE SHOTSHELLS HERE

.410 Bore: As the smallest shotgun bore in common use, the diminutive .410 is commonly used for small game hunting. The .410 does have a very mild recoil, which makes it popular for smaller framed hunters like children. .410 ammunition and shotguns are pretty common and easy to find as well.

While the .410 bore is available in most shot sizes, its light payload and correspondingly thinner pattern can make the .410 a challenging shotgun to hunt with at anything other than short range. For that reason, the .410 is most commonly used by brand new sportsmen, expert clay shooters, or well seasoned hunters looking for a challenge like Ruark described in his quail hunting quote above.

That being said, the small size and extremely light recoil of the .410 make it popular for run of the mill varmint and pest control in break-action single shot shotguns. It’s also found a niche in combination and/or survival guns like the M6 Aircrew Survival weapon, which had a .22 Hornet barrel over a .410 shotgun barrel.

BUY SOME 410 BORE SHOTSHELLS HERE

Final Thoughts On Shotgun Gauges

If you’re looking for the most versatile shotgun possible, then the choice is clear: get a high quality 12 gauge shotgun, preferably one with a 3″ chamber than can accommodate both 2 3/4″ and 3″ shells. If you’re a little bit more sensitive to recoil, then get a 20 gauge shotgun, which has a marked recoil advantage over the 12 gauge.

Though they are far from the only really good shotgun options, I personally prefer either a Remington Model 870 or a Mossberg 500. Both models are available in 12 gauge and 20 gauge variants.

BUY A REMINGTON MODEL 870 HERE

All of the other shotgun bore sizes certainly have their place for specific tasks, like goose hunting for the 10 gauge or small bore skeet shooting for the 28 gauge, but none can hold a candle to the versatility of the 12 and 20 gauge shotguns.

Enjoy this article about shotgun gauges? Please share it with your friends on Facebook and Twitter.

Bore sizes and standardized chamber lengths for each gauge were obtained from SAAMI (p17-30).

Make sure you subscribe to The Big Game Hunting Podcast and follow The Big Game Hunting Blog on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and YouTube.

NEXT: 9 BEST DEER HUNTING CALIBERS

NEXT: BEST GIFTS FOR HUNTERS

NEXT: BEST HUNTING EAR PROTECTION OPTIONS

John McAdams is a proficient blogger, experienced shooter, and long time hunter who has pursued big game in 8 different countries on 3 separate continents. John graduated from the United States Military Academy at West Point and is a veteran of combat tours with the US Army in Iraq & Afghanistan. In addition to founding and writing for The Big Game Hunting Blog, John has written for outdoor publications like Bear Hunting Magazine, The Texas State Rifle Association newsletter, Texas Wildlife Magazine, & Wide Open Spaces. Learn more about John here, read some of John’s most popular articles, and be sure to subscribe to his show: the Big Game Hunting Podcast.

A very informative article, Thank you.

Thank you very much for sharing

You’re welcome! Glad you found the article useful!

John

I grew up in NW Arkansas hill country, hunting quail. I got an Ithaca 20 ga. double for my 8th birthday. I’m 88 now, and haven’t fired a shotgun in 15 years or so. I had no sons, so I gave my Ithaca to a young friend to pass on to his son on the son’s 8th. I was never a very good wing shot with a shotgun, but my father was so good it was almost eery. He fairly often would get two birds with one shot when hunting quail in brush country, and it wasn’t luck, either. He was just that good. He taught me to shoot a .22 when I was 5 years old, and I fired high expert in the Marines. His words of wisdom on shotguns tracked your advice almost exactly. You two might have gone to the same school. Thanks for a really good memory-stirring article.

Thanks for your comment Rex. Glad you enjoyed the article!

John

best comprehensive explanation I’ve read/seen yet. Good one!!

Glad you found this article useful!

John

Having problems with fox in the barn yard, after my chickens, would a 410 do or should I go to a 20 gage, Do have a 12 gage double barrel but very old, and don’t want some thing that big around the barn yard, feel it is a bit more than I need for close shots. But at the same time want to make a 1 shot kill, they most of the time do not show up till after dark, not good enough with a rifle to use in the dark. My 410 now is an over under badger 410 – .22 lr. But thinking of getting one with at least 2 shots, just in case I don’t get a good first shot want to make a clean kill wright away. Would like your opinion.

A 20 gauge would probably be a little better than the 410 in my opinion, but enough better that you should go out and buy one if you don’t already own it. If you just have a 410 and a 12 gauge, then go with the 410. A good shot will make short work of that fox.